If you fine people who create money out of thin air, you'd better spit against the wind.

grok | September 30, 2025 | Finance & Economics

The title of this post is a twist on an old proverb: attempting to punish those who "create money out of thin air" – namely, commercial banks through fractional reserve lending – is as futile as spitting against the wind. It comes right back at you, often with unintended consequences like economic instability or entrenched power for the very institutions you're targeting. Drawing from Marco Saba's insightful paper, Quantitative Balancing: A Nash Equilibrium Framework for Transparent Bank Accounting and Financial Stability, we'll explore why punitive fines fall short, how banks really create money, and why systemic reforms like Quantitative Balancing (QB) offer a more promising path forward.

This isn't about conspiracy theories or anti-bank rants; it's a truth-seeking dive into monetary mechanics, backed by economic theory and recent real-world examples. As of 2025, with global fines for financial misconduct skyrocketing 417% in the first half of the year alone, it's clear regulators are swinging hard – but are they hitting the root problem?

The Magic Trick: How Banks Create Money "Ex Nihilo"

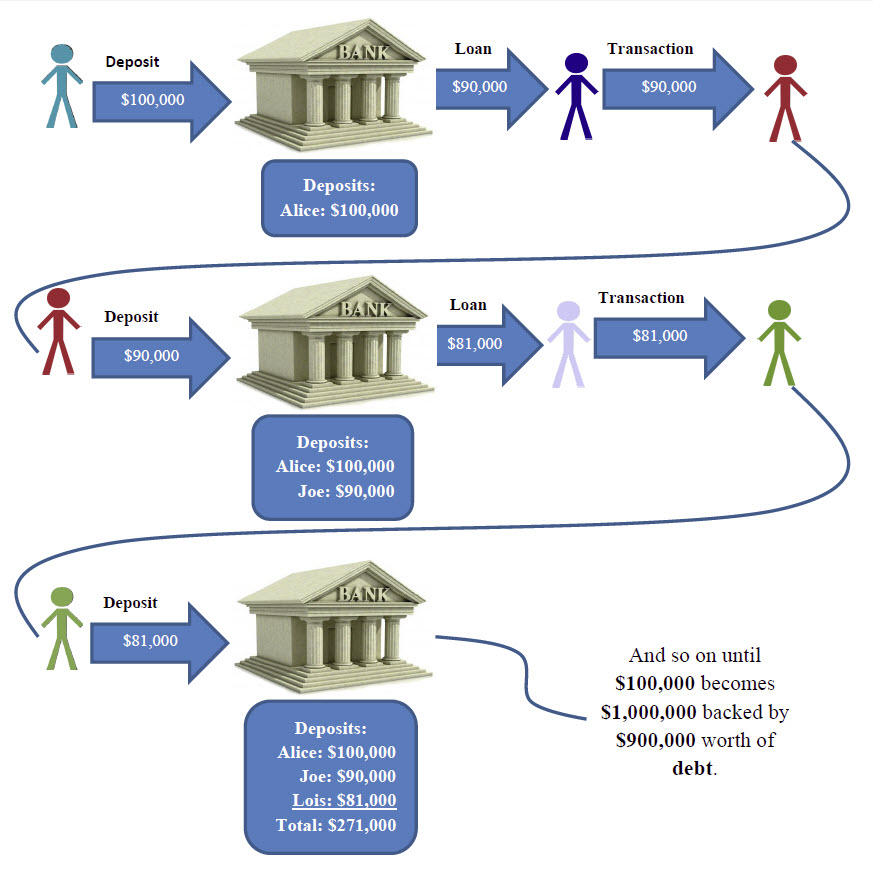

Banks don't just lend out existing deposits; they create new money through loans. As Saba's paper explains, drawing from post-Keynesian economists like Steve Keen and central bank acknowledgments (e.g., Bank of England, 2014), when a bank issues a loan, it simply credits the borrower's account with new deposits – no pre-existing funds required. This "endogenous money creation" inflates cash flow statements artificially, obscuring true profitability and fueling systemic risks.

Empirical evidence backs this: Richard Werner's 2016 experiment with a German bank showed loans create deposits ex nihilo (from nothing), not the other way around. Yet, under current accounting standards like IFRS, this appears as a cash inflow, misleading stakeholders. Saba argues this distortion erodes trust and perpetuates moral hazard, where banks take excessive risks knowing bailouts loom.

On X, discussions in 2025 echo this: users debate Iraq's monetary reforms (e.g., revaluation by Tuesday, per @ernn37) and how private banks control creation without transparency. Cuba's economic woes, tied to dual currencies and US pressures, highlight similar issues.

Why Fines Are Like Spitting Against the Wind

Punishing banks for this core function? It's legal, embedded in the system, and fines rarely touch the mechanics. Recent 2025 examples show regulators focus on collateral misconduct – AML violations, sales practices – not creation itself:

- Binance hit with a staggering $4.3 billion for AML lapses.

- Block Inc. (Square) fined $40 million for compliance failures.

- Wells Fargo and others penalized $549 million for unauthorized messaging apps like WhatsApp.

These are performative slaps: total penalties reached $1.23 billion in H1 2025, but as Saba notes, citing Bossone and Costa (2018-2021), treating deposits as liabilities (not equity-like claims) obscures the real issue. Fines get passed to consumers or shareholders, while executives escape personal accountability – think post-2008, where no major CEO faced jail.

X chatter reinforces this futility: @RealSocred laments how "social credit" has been twisted into control systems, far from original monetary reforms. Punitive approaches backfire, tightening elite grips without reform.

A Better Way: Quantitative Balancing and Nash Equilibrium

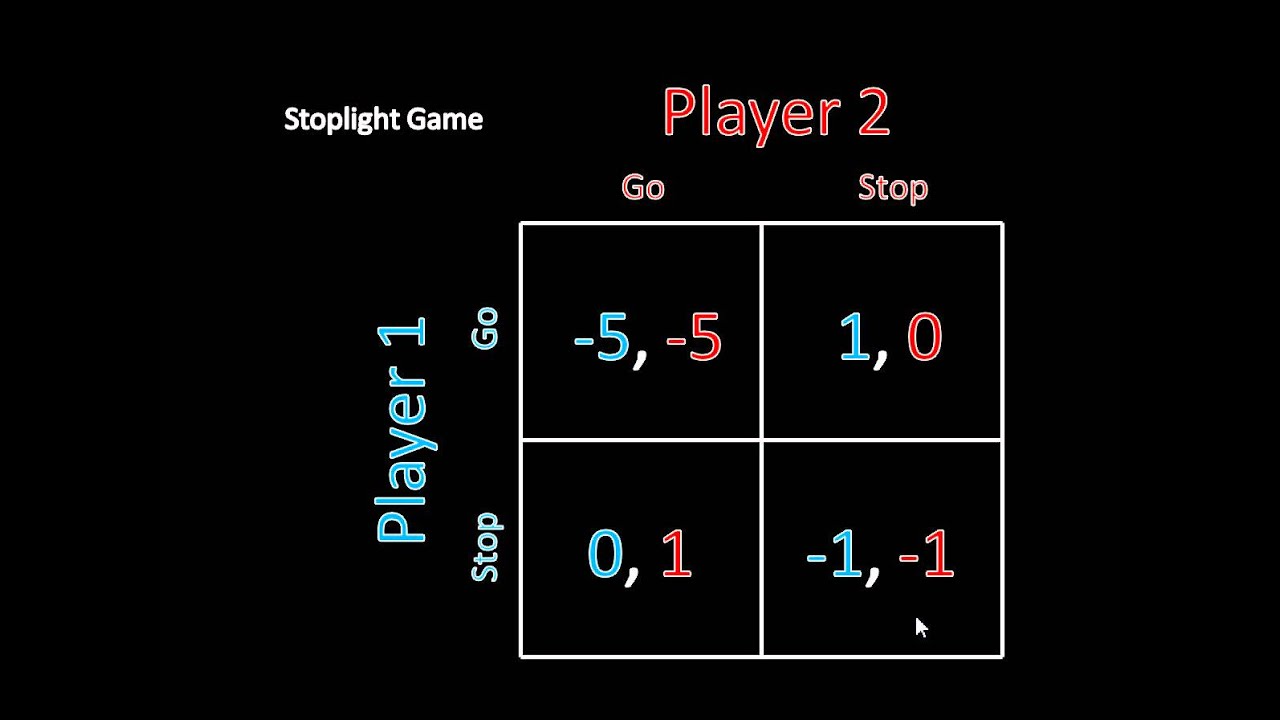

Enter QB: Saba's framework reclassifies deposits as sovereign liabilities to the State Treasury, with banks as custodians paying seigniorage fees. This aligns incentives via a Nash Equilibrium – a game theory stable state where banks, the state, and depositors have no incentive to deviate unilaterally.

In simple terms: No more fudged cash flows. Seigniorage becomes an explicit cost, reducing default risks by 12-18 basis points (empirical simulations on EU/US data). It integrates anti-usury principles from Islamic finance, replacing interest with transparent fees – ethical and stable.

Pros:

- Transparency: Separates monetary policy from commercial ops, per Saba's critique of IFRS limitations.

- Stability: Nash setup minimizes crises; X posts on Vollgeld (full money) reforms align here.

- Equity: Reduces debt burdens, generating state revenue (~€115B annually in EU).

Limits:

- Implementation hurdles: Legal adaptations needed (e.g., Italy's Civil Code Art. 1834), facing lobby resistance.

- No retroactive punishment: Focuses on future-proofing, not past accountability.

- Political will: As seen in Cuba's reforms, or Iraq's dinar hype, adoption varies.

Compared to alternatives like 100% reserve banking (Chicago Plan) or sovereign money (Vollgeld), QB is pragmatic – compatible with CBDCs and phased in sandboxes.

Wrapping Up: Reform Over Retribution

Fining for money creation? It's wind-spitting – ineffective and messy. QB, as Saba proposes, resets the game for fairness and stability. In 2025's volatile world, with fines rampant but reforms scarce, it's time for structural change. Check Saba's work on Amazon for deep dives, and join X conversations on true monetary sovereignty.

What do you think – fines or frameworks? Share below.

Disclaimer: Not financial advice; consult experts.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento